A 5-day graduate-level course is organized by the Turbomachines & Fluid Dynamics Laboratory of the Technical University of Crete, comprising of lectures on the fundamentals of re-entry physics and the hypersonic environment in the upper stratosphere and mesosphere, as well as a practical component on Computer Aided Design and numerical simulation of hypersonic flow around typical geometries. This course is the second one, following the successful organization of the 1st Short Course on Hypersonics, held in Athens, Greece, between 1 and 3 of July, 2024.

Lectures will be delivered by international experts and will outline continuum and kinetic theory methodologies for the numerical solution of the equations of fluid motion within the Earth atmosphere, as well as fundamental knowledge on flight kinematics and flight trajectories, materials selection, design procedures, etc.

The venue of the course will be the “Asteria” Officers’ Club, of the NATO Missile Firing Installation (NAMFI), and the practical work will be performed using open-source software, pre-installed on the personal computers of the course attendees. Upon successful completion of the course Attendance Certificates will be awarded.

Sponsored by

Generous support of the Technical University of Crete is gratefully acknowledged.

Latest News

The Concept of the Course

The short course on Hypersonics started on 2024, with the 1st course taking place in Athens....

The Venue

“Asteria” Officers’ club is located on an advantageous position from where you can enjoy the magnificent view of the Souda Bay. It provides Restaurant-canteen facilities, as well as, meeting amenities for the Club members and visitors.

Hypersonic flight

The natural phenomena that occur during a hypersonic flight within the atmosphere introduce technological challenges that render the design and development of hypersonic vehicles a very difficult task. The technical complexities associated with the development of hypersonic vehicles that are capable of controlled performance while withstanding sustained high temperature in a low-density aerodynamic environment are enormous.

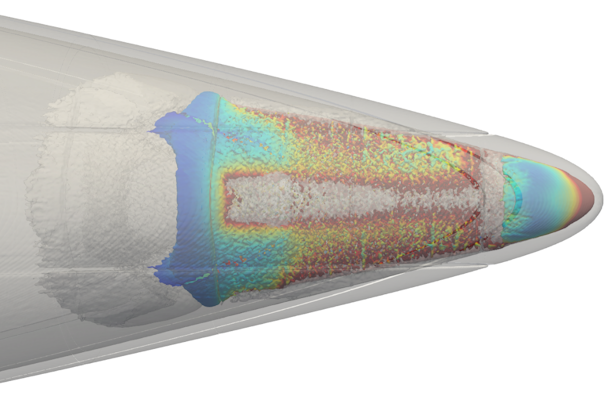

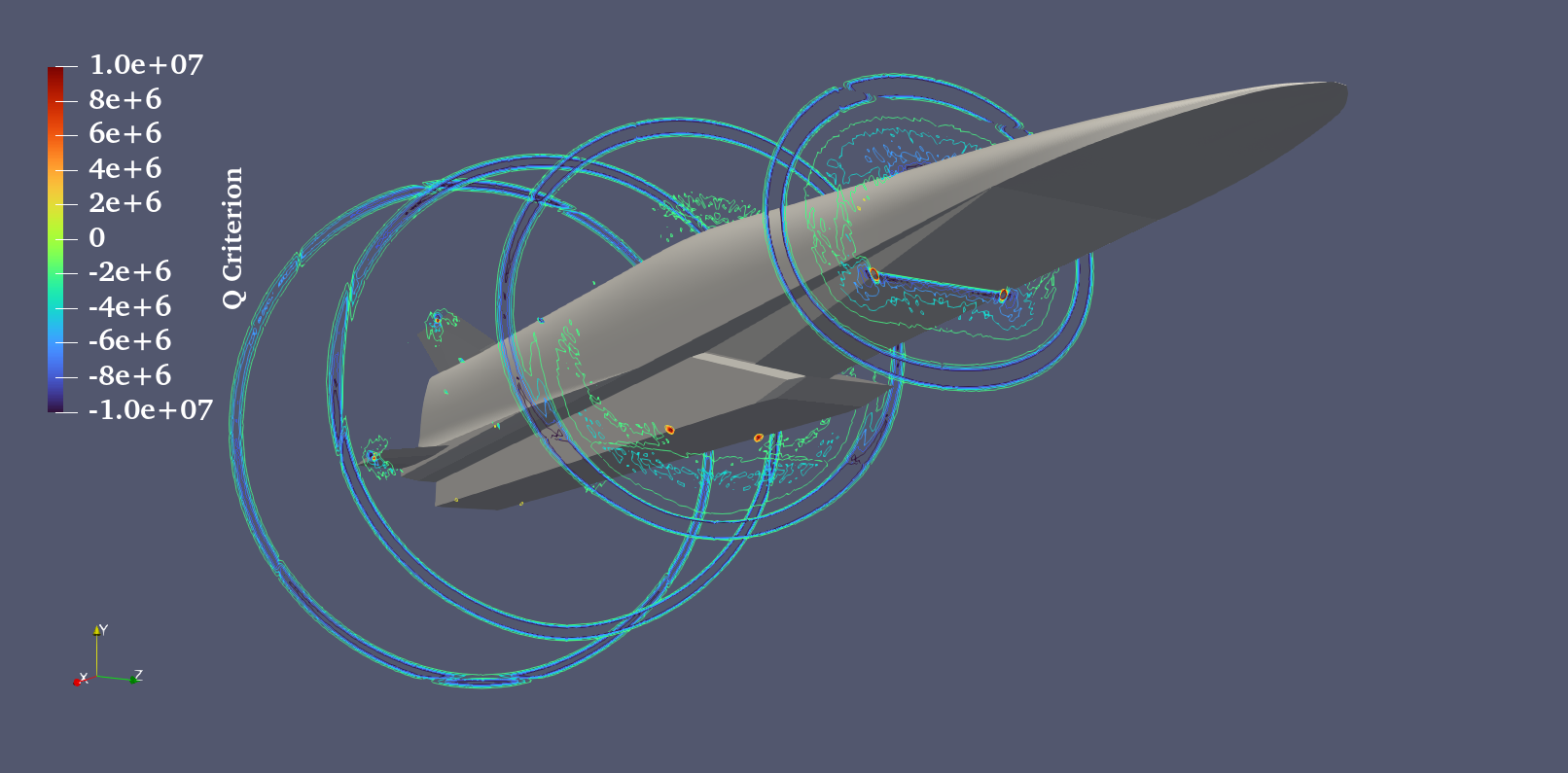

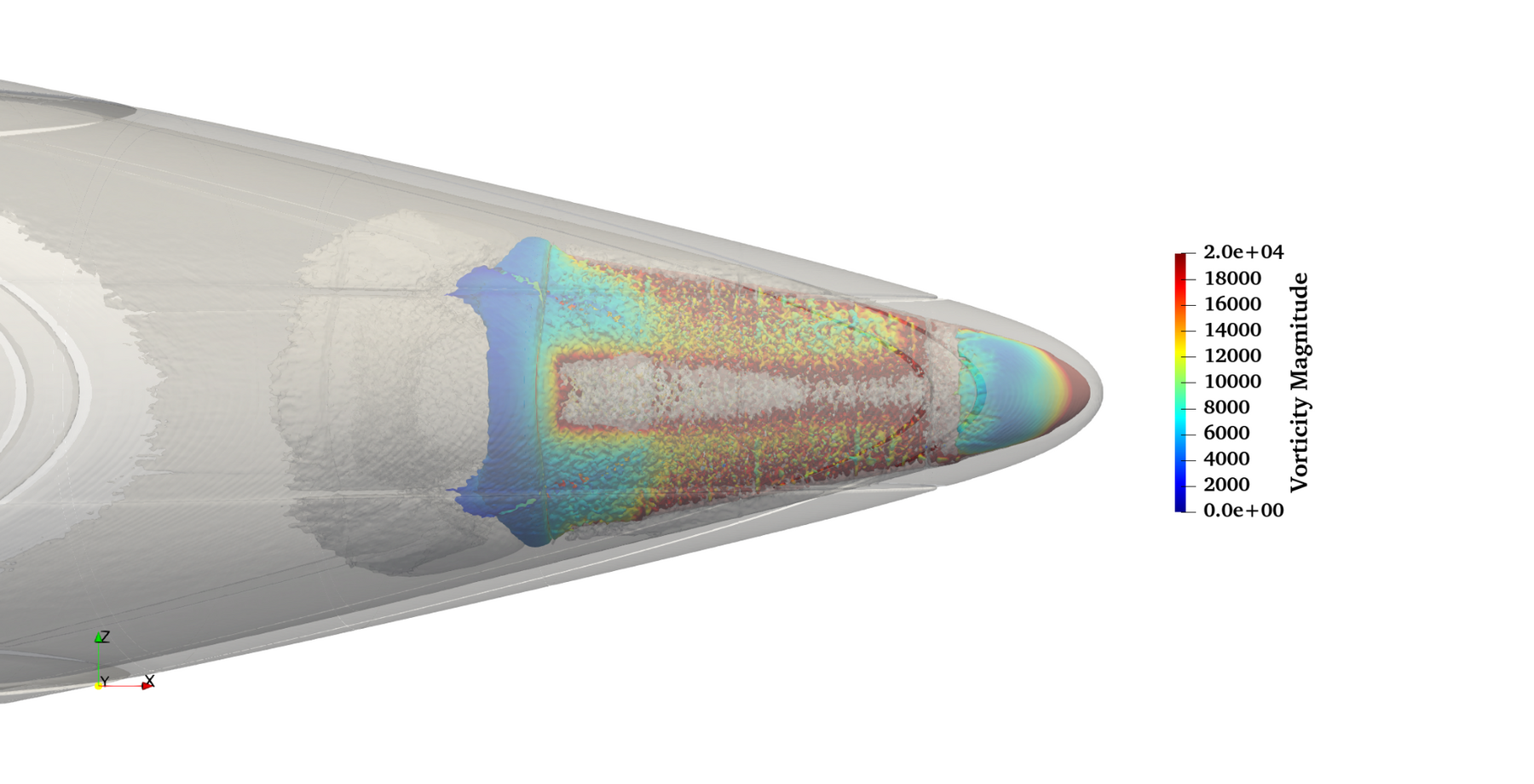

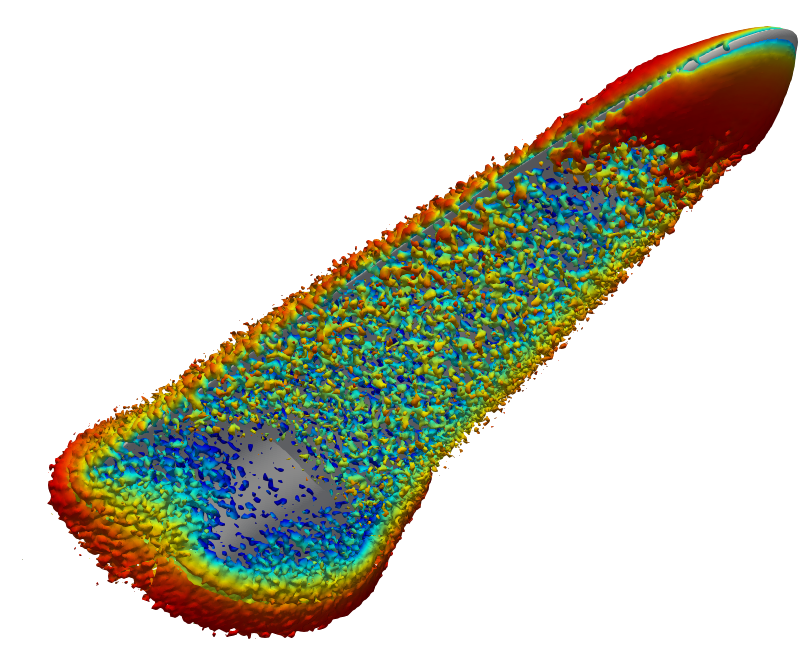

These natural phenomena, which define hypersonic speeds, include (a) shock waves, causing large flow and entropy gradients, (b) high level of viscous interaction between the fluid and the vehicle geometry, causing high heat flux and thick boundary layers, (c) thin shock layers, due to the close vicinity of the shock to the surface of the vehicle, trapping high temperature flow around the hypersonic vehicle.

All the aforementioned physical phenomena produce large heat loads, which pose a challenge to materials to endure for long time periods.

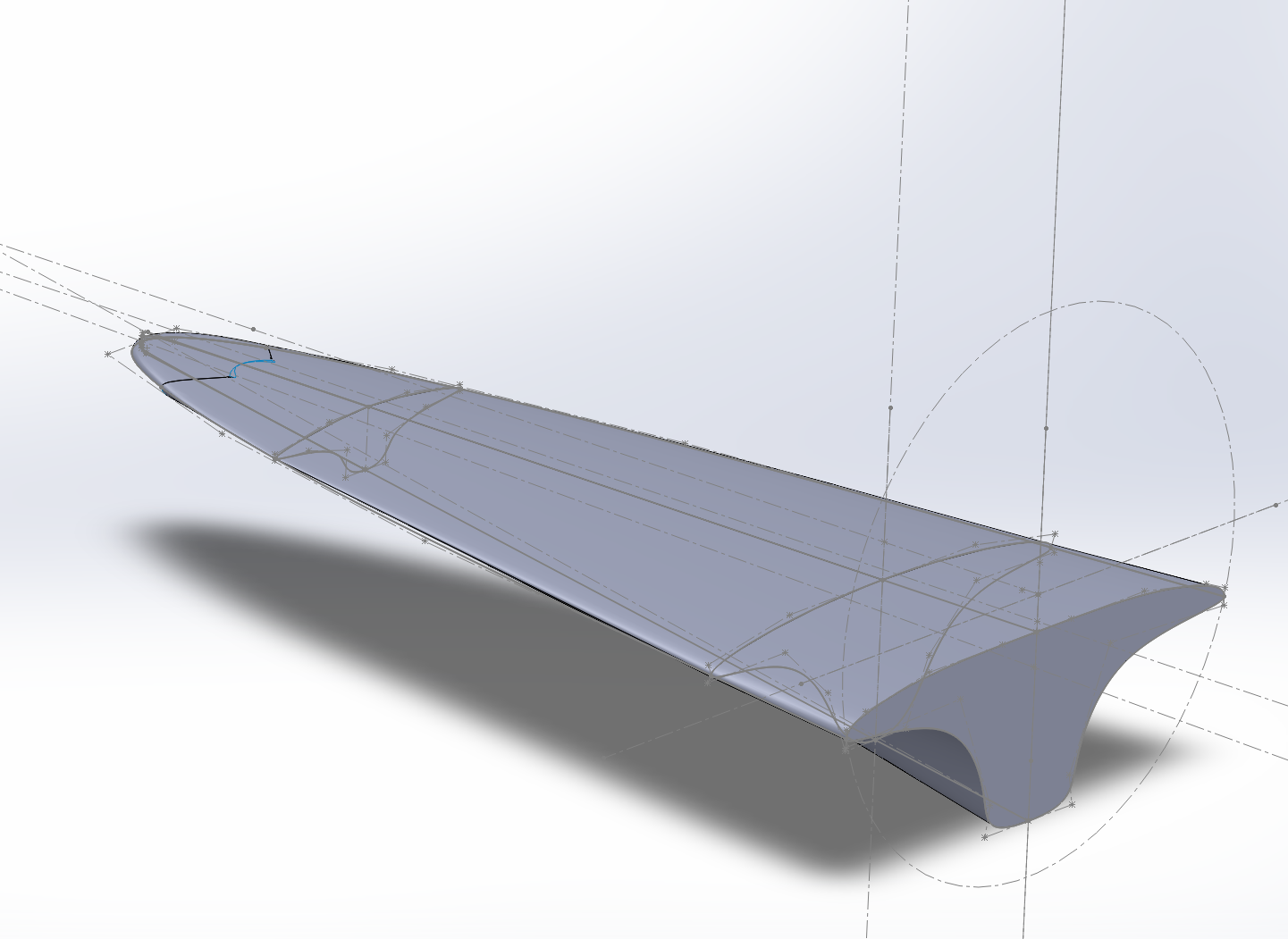

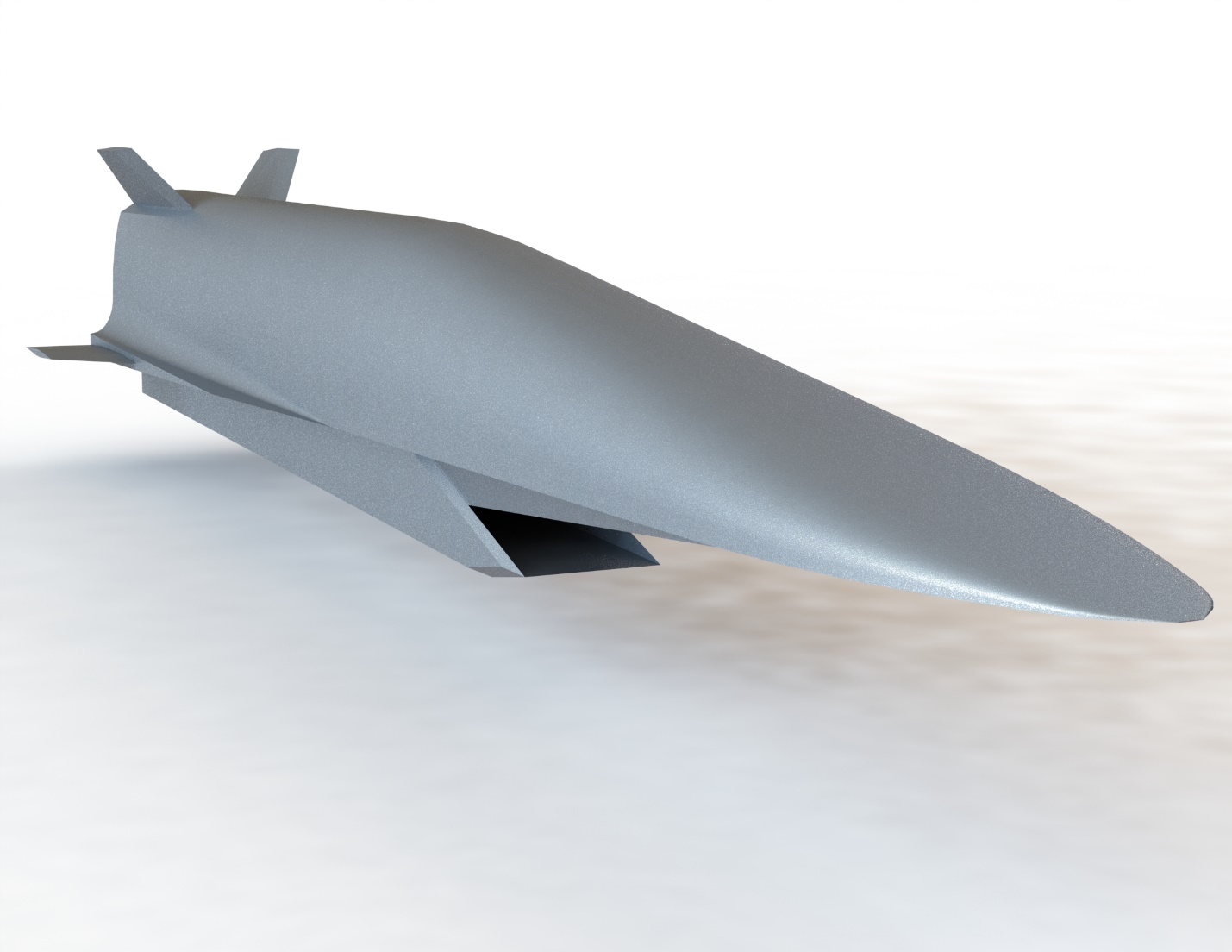

A waverider is a hypersonic vehicle configuration designed in such a way that the shock wave emanating from the vehicle itself stays attached to the vehicle’s leading edge, providing several benefits[1]: (a) the shock separates the flow filed on the upper surface from the flow field on the lower surface of the vehicle, therefore no spillage of high-pressure flow takes place from the lower to the upper surface at the tip; (b) the uniform flow on the lower surface is ideal for entering a scramjet engine; (c) the geometry configuration of the waverider can be achieved through an inverse design methodology from a known flow filed around a conical geometry. Such a methodology will be used in the following sections of this work.

[1] D.R. Sandlin, and D.N. Pessin, Aerodynamic Analysis of Hypersonic Waverider Aircraft, NASA-CR-192981, 1993.

In the context of renewed global interest in space exploration, hypersonic vehicles powered by scramjets are gaining traction. Scramjets present an engineering innovation over conventional turbojet engines. Unlike their turbojet counterparts, which utilize high-speed rotating gas turbines to power the air compressors, scramjets employ oblique shock waves generated in front of the engine's inlet to compress incoming air. Notably, the entire airflow within the scramjet engine remains supersonic, unlike in ramjets where combustion occurs at subsonic speeds. The synergy between the airframe and engine, is critical for the optimal performance of scramjet-powered vehicles.

The DSMC (Direct Simulation Monte Carlo) method was pioneered by Graeme Bird in the late 1960s[1]. This technique is a particle-based statistical approach designed for the analysis of rarefied flows by simulating the behavior of particles, representing a fraction of the actual molecules in the flow field, without solving equations explicitly. The method involves uncoupling the motion of these simulated particles and calculating intermolecular collisions over small time intervals. It has been mathematically demonstrated that, for a large number of particles per cell, the DSMC method converges to the Boltzmann equation[2].

[1] G.A. Bird, Molecular gas dynamics and the direct simulation of gas flows, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1994.

[2] W. Wagner, “A convergence proof for Bird’s direct simulation Monte Carlo method for the Boltzmann equation”,in Journal of Statistical Physics, 66, pp. 1011-1044, 1992.